Georgia Sparling

This is "Why We Write," a podcast of Lesley University. Every episode, we bring you conversations with authors from the Lesley community to talk about books, writing and the writing life.

Julianne Corey

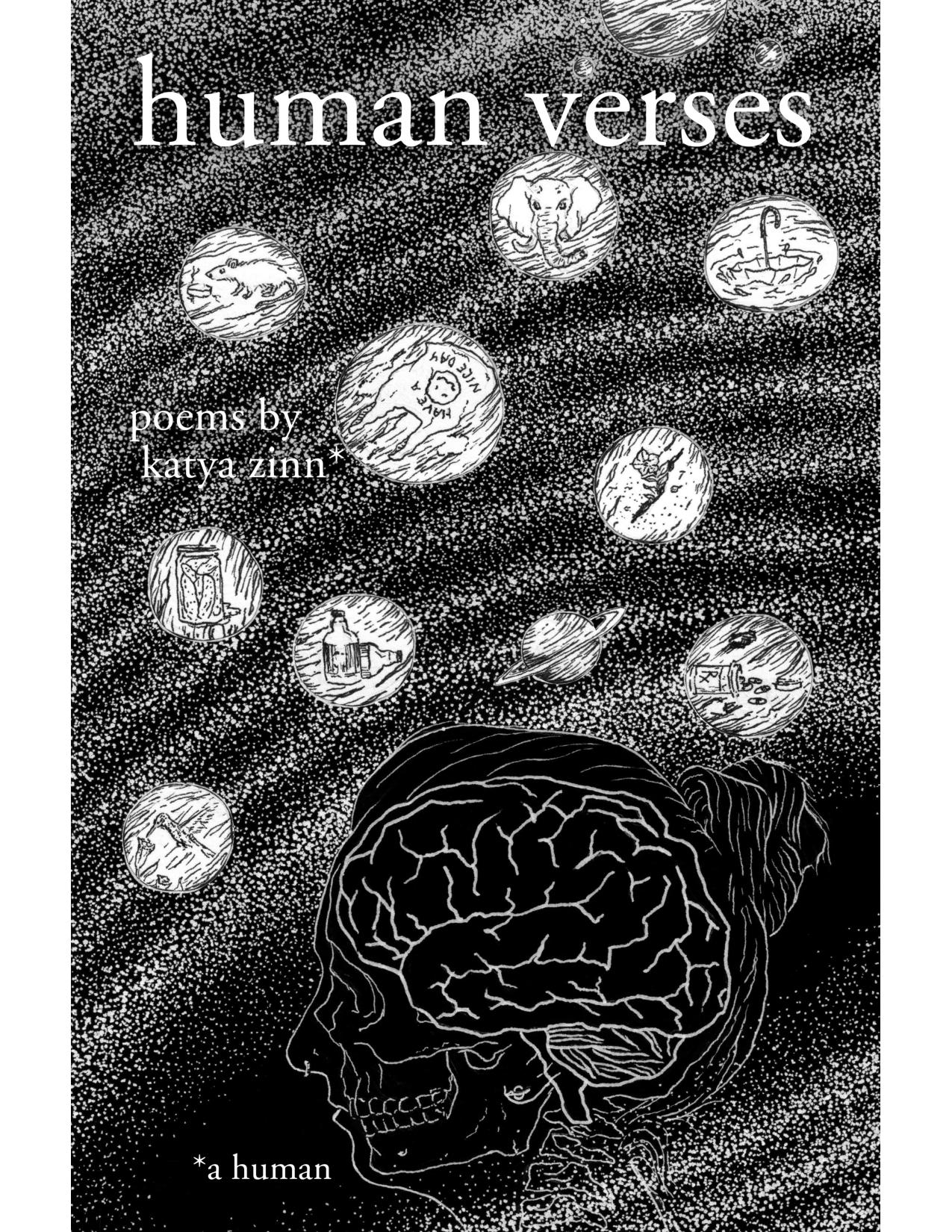

Hello, this is Julianne Corey. I am the Assistant Director for Advising in the Center for the Adult Learner at Lesley University, and Senior Lecturer in Psychology and Applied Therapies, teaching Expressive Arts Therapy undergraduate courses. I am here today to talk with Katya Zinn, a graduate of Lesley University. And we're here to talk about your awesome collection called "human verses." Katya, welcome. Would you introduce yourself and talk about your connection to Lesley, too?

Katya Zinn

Hi, yeah, thank you so much for having me. I graduated from Lesley in 2019, with a Bachelors of Science in Expressive Art Therapy and a Global Studies minor. It was actually at Lesley that I wrote the manuscript that became "human verses." So it's exciting for me.

Julianne

That's really exciting and exciting for me to be conducting this interview and talking with you about this work for a couple of reasons. One, I'm a big fan. And two, I had the privilege of being your academic advisor while you moved through the program. And also because, in addition, you were a student in a course that I teach called Writing from the Body. And I feel like some of the nuggets for some of these poems may have had a bit of germination there. Or at least, I have the experience of kind of being in your sphere as you've been germinating poems and writing and connecting that to healing and transformation. So I'm really excited to talk about these poems with you today.

Katya

Thank you. Yeah, definitely. I mean, I think that I really owe, well, a lot of this book to that class, just because that was where I really learned to integrate mind and body into the writing process. It wasn't something that I had really given much thought to, I think, outside of studying Expressive Art Therapy. So that was a really special experience to me, and definitely one of my favorite classes that I took there, which I'm not just saying, because you're interviewing me. [laughs]

Julianne

Well, thank you for that disclaimer, but I totally see how the body and humanity shows up here. And then, you know, the human in the universe. That is a big part of this collection, as well. And so I want to start talking about that title, "human verses," and how verses comes into, really, the whole design and structure of this collection.

Your table of contents, grouping these poems into different types of verses, different uses of the word "verses". So "vs." period, as in almost like, I kept thinking about boxing matches, like, you know, someone versus someone else, or, you know, man versus nature, something like that. And "verses" also come through this sort of universe and multiverse and human verse, and all of these parallel universes is a big, kind of overarching theme of this collection. And then, of course, it's a collection literally, of verses.

And so that integration of the themes that come through the different uses of the word. And then another theme is really just the way that you play with crafting multi-meaning words, right? Homonyms and homophones and multi use of multi verses. So I wonder if you would just talk for a little bit about what preoccupies you with that and how does that inform your writing and how you're thinking about your themes and your poems and putting them together?

Katya

Yeah. I mean, I think well, first of all, I'm so glad that you picked up on all of that. You know, I'm never sure how well something that I'm trying to convey actually comes through. Because I'm, you know, sort of too close to it, I think, to see how it's how it's being read. But I think that the use of the three different sections to kind of each give a new meaning to the title was, sort of, a.) my way of just kind of cheating with the fact that I have to pick one title. And that's always one of the most difficult parts for me, I think, about writing. The title carries so much weight, and there is so much that you want to convey through the title and-

Julianne

And to somehow encompass everything. Right?

Katya

Right, right, exactly. And, you know, the themes of the poems that are in this book are just so broad and kind of universal. And so the way that the title is used is kind of meant to reflect this journey through the spectrum of human consciousness, which also has, coincidentally, a lot to do with my time at Lesley. Because I took a Transpersonal Psychology class my senior year, that was really pretty transformative for me.

The first time that you see the word "versus," as in the combative contexts, those poems are written from the, sort of, lower end of this enormous spectrum of what human consciousness can contain, which is the phase that I think, you know, a lot of us end up in in earlier stages of healing. And one of the most valuable things that I learned, you know, through Transpersonal Psychology and through expressive therapies is that anytime you deny something, you create this internal conflict. You create this boundary that needs defending on both sides. And so the poems that are in there deal with kind of,trying to make sense of denying trauma and denying the ways that that kind of changed me as a person and intrapersonal, interpersonal conflict.

And then the second time that "verses" is used is, as one word, because I was really fascinated by this idea of the universe and human verse. Kind of sounding so similar, A lot of the inspiration for the poems in this book came from, kind of, thinking of every human being as not just an individual, but an entire universe. You know, we are a product of our perception and we're the sum of every single experience, good or bad or indifferent, that we've carried in our entire lives. And this kind of working towards a greater integration of self and landing more grounded in the body and coming to see yourself as a whole, you know, the goal is that people will read this and find that it fears their experiences or will feel seen or heard by reading those poems and seeing that as an opportunity to write those verses. Write those verses in lines of poetry and leave them there and have them exist outside of the self and kind of bring closure and healing to some of those experiences.

Julianne

Really interesting the way that the different ways of conceptualizing self-concept and self process through those different verses, right? You know, what I kind of heard you say was that inter-, intra-struggle between the self and other, or different parts of the self, and then that broader kind of exploration of all of the different parts of the self, the wholeness within a human verse or a microcosm of the universe. And then that externalizing self and being able to see it, and witness it outside of yourself, and that is a wonderful reflection of the way that we use art. That we use art to heal and make sense of the world.

The themes that are present within the multiverse, as you refer to it in some poems, there's really this duality, I think, that you're exploring between art and science. And I know that science is a big part of your background, and in the way that you're utilizing poetry. You know, you're utilizing an art form, for navigating and finding, seeking some understanding around difficult and dramatic experiences, and maybe even transforming, right? And the themes that you're using in that are largely drawn from science. So I'm wondering if you'd talk with us for a few minutes about how those worlds kind of co-mingle for you as a poet?

Katya

That's such an interesting question because those are, not just as a poet, but such central themes, I think, to my life in general. I was raised by two scientists. Everyone in my family is, you know, my father is a neuroscientist, my mom is a biochemist. My brother is a statistician, he does mathematics. And so, obviously, growing up as a kid that was only interested in art, and music, and poetry and everything that was creative, and I've never been interested by questions that have one answer. I've always been just so much more interested in questioning, and I think that, you know, understanding the world and what we view as intelligence is so much more than the questions that you know the answer to. It's the questions that you ask.

And I think that just circling back to this idea of, kind of, internal conflict as existing lower on this human spectrum of consciousness, that was something that I really struggled with my entire life because the ways that I made sense of the world were so incredibly different from the ways that my family processed reality. You know, I grew up in a family where emotions were very much sitting outside of rationality and emotions were treated as not something to be felt, but something to be empirically justified, rationalized, and then fixed. Because they didn't have a place in, you know, so called "logical conversations."

And I think that what people miss when they place science so far out of the realm of art and other creative pursuits, and view science as inherently objective, is that the more that you learn about science, the more that you realize that it's actually not. And so learning about scientific concepts initially as a way to kind of understand and accept myself and the way that I process the world and somehow learning that, you know, in terms of trauma, such a huge aspect of trauma, is the self-denial piece and this, kind of, imposter complex that-- I can't actually have post-traumatic stress symptoms, that's for people who have real trauma, right? An so viewing that through the lens of, you know, the hyperactive limbic system.

Julianne

Yeah, what can be measured, right? And what can be quantified, and seen on an MRI and-

Katya

Right. [laughs] Exactly. And that initially began as an opportunity to try to understand my own experiences better, but became, through exploring it in writing, I realized that the more that you learn about science, the more that it does start to feel like art. If you think about, you know, theoretical physics, these concepts of reality itself as being inherently subjective, and you know, Schrodinger's cat, right? The perception of matter, the measurement of matter actually influencing the ways that matter takes up physical form. So reading that and realizing that, to exist as a human being, like the human experience, which is like, pretty bold statement for me to make at like, you know, 24-25 to be like "This is my thoughts on what it means to be human," but- [laughs]

Julianne

[laughs] That's also an inherently part of young adulthood, right? It's really, kind of, staking your claim on those theories that are going to guide your choices, right?

Katya

That's true. Yeah, yeah, that's true. And I think that, you know, the conclusion that I came to that really informed all of the poems within this book was that we have this illusion of occupying a shared reality with other people. But in actuality, we're all sort of ensconced within these self constructed universes and the way that we perceive everything that we interact with becomes our reality.

Julianne

I think, you know, thinking of a few of the poems in the collection, right now, when you're talking about this sort of distinction between the universe that we think we're all inhabiting [laughs], and how that can show up as very different universes and this concept of moving around in parallel universes. I'm wondering if you might want to read a little bit from one of the poems and I think, "Theories of the Human Verse." I'm wondering if you might want to share a little bit?

Katya

Sure. Yeah. So this is "Theories of the Human Verse." "Let's talk about quantum physics. Let's talk about things that only matter when they're measured, like particles and waves and abandonment. Let's talk about parallel universes. Let's talk about decisions and indecisions and how each one we make or don't make splinters this cosmic now into infinite and equally probable realities. Let's talk about all these dimensions of ourselves, the ones together and the ones still searching for a love that's both salvation and ruin until we find out which. Let's talk about gravity. Let's talk about this inexplicable attraction, this magnetic madness, this need to bury every piece of myself inside you, stitch you up, and then sew shut the fabric of the universe so you can never leave. Let's call that gravity. Call it the intergalactic forces of shared possibility reaching, pulling lonely planets across a vacuum of uncertainty searching for symmetry.

Let's talk about nuclear fission. Let's talk about our first lesson that splitting creates unstable parts and all the ways we find not to listen because even now, I'm still finding fragments of myself on your shoelaces. I know. None of us are really one person. We are all entire universes, concentric structures of decisions and indecision than parallel planes of the planetary possibility pressed between particles destined for collision. Let's stop calling it mental illness and start calling it extraterrestrial sensing. This ability to contain infinities of alternate selves and their alternate worlds inside the solar system of the skull.

Let's talk about wormholes and black holes and infinite ways to lose yourself inside a timeless wasteland of what might have been. Let's talk about poetry and what a volatile science it is to expand words into worlds we will never inhabit. Talk about Thomas Young, first to discover light behaves differently when observed and Galen Strawson, first to speculate consciousness itself lends matter its physical form. And finally, this poet possibly first to extrapolate, then maybe it is only our certainty in the capacity of things to remain themselves that allows them to occupy space across infinite possible realities. For instance, let's talk about yesterday over breakfast, when I asked again if you were intending to stay and just like that, you vanished. Let's talk about entanglement, quantum or otherwise, and how in all the ways I told myself you would save me, letting me go was the last one I could ever have predicted."

Julianne

Well, that's definitely an amazing illustration of science and what can be measured and emotions co-mingling. I love the line about expanding worlds into words, which is really, I think, what you're doing here. And when you bring that into the poem, it's under the context of "let's talk about poetry, and of what a volatile science it is," misquoting you here, "to expand words into worlds we will never inhabit."

Katya

Just learning about the multiverse theory and parallel universes and quantum physics and everything. It's always something that I've just been incredibly fascinated by. This idea, right, that at the furthest reaches of science, it starts to look more like philosophy, that theoretically, right, every decision that we make, creates an alternate universe in which we didn't make it wherever there is uncertainty. And, to me, that's the closest thing that I can think of to describe what it feels like, for me, to deal with PTSD is that there's theoretically, an alternate universe in which every single trauma that anyone has suffered, didn't happen. And there's a you in that universe, and there's a you in this universe. And for better or worse, you know, those two individuals are entirely different.

And I think, just in terms of my own journey towards approaching healing and the ways that art and science have both come into that, I read countless, self-help books on overcoming trauma, countless works by different authors on their own process of healing and dealing with their own trauma. And I think so much of what I read was focused on kind of overcoming trauma as this like oblique other that you move past and return to who you were. That that is ultimately the goal. And--

Julianne

And this is not that. Like what you're describing is not that.

Katya

Right. And I don't just think that didn't resonate with me so much, because I think that trauma isn't something that we necessarily overcome. And I don't think that has to be a pessimistic statement. I think that trauma is something that we learn to live with and make peace with and make peace with living in a universe, in a reality, that's been fundamentally altered. And when somebody denies you your humanity, they quite literally fracture your reality because it splinters, you know, the consciousness creating the universe that you occupy space in. And I hadn't come across anything in my own reading that dealt with trauma in that way. And so I wrote it. [laughs]

Julianne

And when you use that metaphor, it's in some way, it's like adopting a model, right? Like you're adopting a model that exists. We're not saying, maybe traumas like this or that. You're saying, you know, "here's a model that exists in the world, it exists in the universe. It, There's a measurement and quantification to back this up," right? It's that theory of parallel universes can contain something like what you experience of the experience of a reality changing. So fundamentally- I also, I loved hearing. I'm so glad that we have an opportunity for you to read from that one because there's this rhythm, right? There's this repetition that the phrasing creates- let's talk about, let's talk about, let's call it. It hadn't really occurred to me, reading it on the page, but when you were reading it aloud, it struck me that it was a little bit like a rallying cry. Did you feel like that at all when you were writing it?

Katya

My background is in spoken word. I've been really involved in in the slam community competitively, performing poems in a set three minutes. And in some ways, that's an opposite goal to writing a poem because when you're writing a poem for the page, you want it to have to be picked apart and put back together and have the meaning not necessarily exist right on the surface. But when you're writing a poem for the stage, you have three minutes to say what you need to say, and people better know what you're saying, if you want to get a good score.

And so, kind of bridging those two worlds and trying to figure out how to, hopefully, create something that people can hear and feel heard and that people can see on the page and feel seen by and gain something from it that might not exist, the first time hearing it. So that's why I play a lot, I think, with kind of, white space and the ways that words lie across the page.

Julianne

Yeah, there's some real syntax experimentation in this. When the folks who are listening pick up your collection of poetry, because I know they will, and they're looking at this poem on the page, there's a lot of changes in syntax. What's going on there for you as a writer, and as you know, as you're making decisions about the page and the space?

Katya

Yeah, I think it's interesting. I thought this was, like, a universal experience until I started actually talking about it and seeing people's expressions. When I hear poems or envision poems in my head, they're three-dimensional. And I see poems as having different shapes. And when I can perform a poem, when I can say the words out loud, I can use three-dimensional space, right? But on the page, it has to exist in two dimensions. And so that's always a really big challenge because there isn't enough grammar and punctuation in the world [laughs] that can make a poem look on the page the way that it exists in my head. So playing with white space and playing with grammar and syntax and punctuation allows me to get closer to what that looks like in my head.

Julianne

And maybe thinking about the way that poems move, and how they would be spatially related has, maybe, at least a reverence for treat your Expressive Arts Therapy training. I mean, maybe that's what drew you to something intermodal or, there's like an inter-modality to these poems on the page or that you're trying to express or represent somehow. That's really pretty cool.

Katya

Thank you. Definitely, yeah. And in terms of expressive therapy, learning to write from the body-

Julianne

Oh, you're speaking my language.

Katya

[laughs] -has been really helpful too, I think, because when I took that class, I was still very much in a space of having this huge disconnect between mind and body that I think happens whenever anybody deals with dissociation. And so a lot of the exercises on the first try, like, I just didn't get it. I was like, "I don't even want to think about the fact that I have a body." I try not to--

Julianne

Not the easiest thing.

Katya

Yeah. But then, just discovering that, and where poems live, you know, within your body, like I think different poems come from different places within your physical form. And so getting to explore that is really fascinating as well.

Julianne

I'm thinking a lot about the poem that you wrote about your hands. And this conversation around where poems live and where we may not really want to listen so much to the language of our bodies. To, kind of, start to unravel some information that's really pertinent to healing trauma and making sense of trauma. There's a poem "Dermatillomania." There's a little bit of a refrain in this poem around not wanting to write this poem. And the first line is, "I do not want to write this poem about my hands." And that continues to come through, even though you are literally in the act of writing a poem about your hands. And I wonder if, you know, we can talk about this poem specifically or maybe even in general, around the resistance of looking at the vulnerability of the body.

Katya

I mean, if there's anything Expressive Therapy has taught me, it's that if you don't want to write about something, or whatever your medium is, if you don't want to go deeper into something, it's probably exactly because you should and you need to. What I think is so interesting that I don't even fully understand is how the body, or the piece of art that's created through that, whatever it is, can know before we do, what is there. Because I didn't know why. You know, I had this habit my entire life of-

Julianne

Can you tell us, for a minute, just kind of an overview about dermatillomania?

Katya

Oh, yeah, it's kind of, a OCD related body focus, repetitive behavior of just picking at skin. And so a lot of people with it, the hands are a big one, the cuticles. And it's something that I've struggled with my entire life. That people who do notice always seem to think that like, "Oh, have you tried this? Have you tried-" And that actually, I talk about in the poem, that--

Julianne

Unsolicited advice, right?

Katya

Right. And there's no magic silly putty, you know, that's gonna stop that from happening. That it's a compulsive thing. I don't think I had, really, an understanding at all of why I did that until I wrote about it.

Julianne

I wonder if that mirrors in some way your experience in your relationship with trauma work and healing.

Katya

For me, something that has been really valuable in terms of working through my own trauma is something that I like to call the reverse Golden Rule. Right? So the golden rule is you treat other people how you want to be treated. And then, on the flip side of that, is learning to treat yourself with the same compassion and kindness and care that you would extend to somebody else.

Julianne

Yes. Yes. Well, you said people weren't really listening until you were able to share your story and tell your story.

Katya

Right.

Julianne

Did poetry make that more palatable for you? You know, there's a kind of a phrase called "tell it slant," because, sort of, the idea of that is that we may have more access to different parts of the story by bringing in imagery and allegory and alliteration and then meter and things. Is there an element of that for you?

Katya

Yeah, absolutely. I mean, I think it's given me a voice back that I didn't feel like I had for a really long time. And, I mean, one of the most powerful aspects for me about that is hearing that when people heard me tell my story, that it gave them the courage to be able to tell theirs.

Julianne

Yeah. I'm looking forward to seeing what comes next but also really, to kind of savor what came through these poems.

Katya

Thank you so much.

Julianne

Thank you so much for talking with us today about this powerful, brave work and how exciting the publication of your first collection of poetry, Katya. Thank you.

Georgia

Thank you for listening to "Why We Write." Katya Zinn's debut book of poetry, “human verses,” is out now from Finishing Line Press. We hope you'll check it out. Head on over to our episode page for links to her book, an article we wrote on Katya when she was graduating from Lesley, and more. The link is in the show notes. We'll be back the first Tuesday in April for a special series that we're doing in honor of National Poetry Month. Don't forget to subscribe to this podcast so you don't miss an episode.